Where There’s Smoke (Part 3)

Fire your imagination! Ignite your passions! No, it’s not a commercial for some new fragrance. It’s chapter three of our rundown of cartoons dealing with fire and firefighters. Hopefully, we’ll keep things sizzling enough to develop heated discussion, and add a little spark to your life.

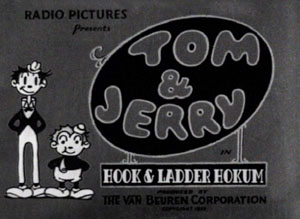

We begin with what may be the earliest screen credit for a legendary director – a credit which he would not even take in his own name. Frank Tashlin would refer to himself by the nickname “Tish Tash” in the production of Hook and Ladder Hokum (Van Buren, Tom and Jerry, 4/28/33 – Geo. Stallings/Tish Tash, dir.)

Tom and Jerry (Van Buren’s Mutt and Jeff counterparts, not the cat and mouse) kill time at the firehouse with the usual game of checkers. Primary difference from Flip the Frog’s game is that Jerry’s checker conducts its jumps under its own power, allowing Jerry to clean the board. A poorly-drawn caricature of Ed Wynn appears in a picture frame as “Our Chief”, breaking into trademark hysterical laughter and his catch-phrase, “So-o-o-o-o”. Wynn was a rising star of a radio show sponsored by Texaco, makers of “Fire Chief” gasoline – and so was traditionally pictured wearing a fire chief’s hat. Wynn would become a recurring cameo in such attire in later cartoons which have little else to do with fire, including Warner’s I’ve Got To Sing a Torch Song (Merrie Melodies, 9/23/33) (which gets his look right but not the voice), and Columbia’s Gifts From the Air (Color Rhapsody, 1/1/37). The portrait continues laughing, while aggravated Tom throws a spittoon at it. Instead of being hit, the portrait reaches out of the frame, catches the spittoon, and throws it back at Tom for a direct hit, knocking him woozy. Jerry prepares for bed, removing his uniform piece by piece as he walks, with each article of clothing arrayed at a distance from one another on the floor, on wall hooks, on trapezes, etc. as he goes, then hops into the sack. To, also strips down to his BVD’s, and brushes his teeth (despite the fact they are false ones he ultimately removes and puts in a cup). Tom joins Jerry in bed, but greedily rolls himself up in the entire blanket like a coil, unnoticed by Jerry as he sleeps. Tom’s mot much of a fireman, as he has trouble with even the simple flame from the bedside candle, unable to blow it out – so he smashes the whole thing with a mallet (something Mickey Mouse had done in the preceding year in “Mickey’s Nightmare”).

Tom and Jerry (Van Buren’s Mutt and Jeff counterparts, not the cat and mouse) kill time at the firehouse with the usual game of checkers. Primary difference from Flip the Frog’s game is that Jerry’s checker conducts its jumps under its own power, allowing Jerry to clean the board. A poorly-drawn caricature of Ed Wynn appears in a picture frame as “Our Chief”, breaking into trademark hysterical laughter and his catch-phrase, “So-o-o-o-o”. Wynn was a rising star of a radio show sponsored by Texaco, makers of “Fire Chief” gasoline – and so was traditionally pictured wearing a fire chief’s hat. Wynn would become a recurring cameo in such attire in later cartoons which have little else to do with fire, including Warner’s I’ve Got To Sing a Torch Song (Merrie Melodies, 9/23/33) (which gets his look right but not the voice), and Columbia’s Gifts From the Air (Color Rhapsody, 1/1/37). The portrait continues laughing, while aggravated Tom throws a spittoon at it. Instead of being hit, the portrait reaches out of the frame, catches the spittoon, and throws it back at Tom for a direct hit, knocking him woozy. Jerry prepares for bed, removing his uniform piece by piece as he walks, with each article of clothing arrayed at a distance from one another on the floor, on wall hooks, on trapezes, etc. as he goes, then hops into the sack. To, also strips down to his BVD’s, and brushes his teeth (despite the fact they are false ones he ultimately removes and puts in a cup). Tom joins Jerry in bed, but greedily rolls himself up in the entire blanket like a coil, unnoticed by Jerry as he sleeps. Tom’s mot much of a fireman, as he has trouble with even the simple flame from the bedside candle, unable to blow it out – so he smashes the whole thing with a mallet (something Mickey Mouse had done in the preceding year in “Mickey’s Nightmare”).

No sooner has Tom closed his eyes, than an alarm bell on the wall phone rings. The phone develops a face, and adds to the noise by letting out a whistle from its mouthpiece. Still coiled in the blanket, Tom shimmies his way over to the phone, and lifts the receiver. Instead of a voice, he finds flames from a conflagration shooting out of the ear-piece! The boys spring into action – quite literally. Jerry engages in a marvelous series of acrobatic leaps and somersaults, re-entering all the previous articles of clothing where he had laid them. The boys reach the hole to the engine room below, bit there is no pole – only a nearby sink on the wall. Tom bends the faucet pipe as if it were made of rubber, stretching it to extend over the hole, then turns on the water. He and Jerry then grab hold of the flowing water and ride it downstairs. (There is no sign of a drain below, and the boys leave the water running. I guess fires are a no-no, but floods are okay.) Tom abruptly wakes up the station’s fire horse, asleep in a hammock, by cutting the rope suspending the hammock on one side. The pumper engine and crew are soon off to the races. En route, Jerry reveals that the pumper boiler isn’t exactly what it’s cracked up to be, as the structure is completely detachable from the engine chassis, and entirely empty. Jerry keeps up appearances, by placing a lit kerosene lamp inside the boiler cylinder, providing puffs of smoke out the top as if operating efficiently. The next gag is undoubtedly Tashlin’s – as we would see him use a variation on it again in a subsequent fire cartoon. The blaze at a three-story apartment house shoots out flames from the windows, lighting up the sky as they form into the shape of the words, “HELP” and “HURRY”. Arriving at the scene, the boys have the usual hose trouble, with only drops emerging for Jerry. Tom has to breathe some life into the hose, by playing a small flute, performing the music of an Indian snake charmer. The hose coils and rises to an upper story window, where a bald, goateed old farmer-type stands in his nightshirt, repeatedly calling for “Water”. He gets it, as the hose aims directly at him, suddenly blasting him with a full-force jet of H2O, which pushes him backwards across the entire floor of the house, and out a window on the opposite side.

No sooner has Tom closed his eyes, than an alarm bell on the wall phone rings. The phone develops a face, and adds to the noise by letting out a whistle from its mouthpiece. Still coiled in the blanket, Tom shimmies his way over to the phone, and lifts the receiver. Instead of a voice, he finds flames from a conflagration shooting out of the ear-piece! The boys spring into action – quite literally. Jerry engages in a marvelous series of acrobatic leaps and somersaults, re-entering all the previous articles of clothing where he had laid them. The boys reach the hole to the engine room below, bit there is no pole – only a nearby sink on the wall. Tom bends the faucet pipe as if it were made of rubber, stretching it to extend over the hole, then turns on the water. He and Jerry then grab hold of the flowing water and ride it downstairs. (There is no sign of a drain below, and the boys leave the water running. I guess fires are a no-no, but floods are okay.) Tom abruptly wakes up the station’s fire horse, asleep in a hammock, by cutting the rope suspending the hammock on one side. The pumper engine and crew are soon off to the races. En route, Jerry reveals that the pumper boiler isn’t exactly what it’s cracked up to be, as the structure is completely detachable from the engine chassis, and entirely empty. Jerry keeps up appearances, by placing a lit kerosene lamp inside the boiler cylinder, providing puffs of smoke out the top as if operating efficiently. The next gag is undoubtedly Tashlin’s – as we would see him use a variation on it again in a subsequent fire cartoon. The blaze at a three-story apartment house shoots out flames from the windows, lighting up the sky as they form into the shape of the words, “HELP” and “HURRY”. Arriving at the scene, the boys have the usual hose trouble, with only drops emerging for Jerry. Tom has to breathe some life into the hose, by playing a small flute, performing the music of an Indian snake charmer. The hose coils and rises to an upper story window, where a bald, goateed old farmer-type stands in his nightshirt, repeatedly calling for “Water”. He gets it, as the hose aims directly at him, suddenly blasting him with a full-force jet of H2O, which pushes him backwards across the entire floor of the house, and out a window on the opposite side.

The man struggles to regain a footing inside the house, running atop the water stream, climbing upon it hand-over-hand, etc., and finally gets back inside and over to the original window. Meanwhile, down below, the horse sets up a running gag, attempting to help with a small pail of water and a farm water pump. He fills a first pail, and prepares to throw it through a ground-floor window. However, a flame leaps out the window to toast the horse’s hoofs, causing him to waste the water on quenching his feet rather than extinguishing the main blaze. Back at the upper window, the old man nervously considers jumping, while Tom and Jerry position a fireman’s net below him. He jumps, but bounces off the trampoline surface up to the roof, and down the chimney, reappearing at the window in blackened form, to shout an Al Jolson, “Mammy”. The horse tries things again, but takes a burn to the tail, leading him to return to the water pimp just to soak his rear end under the pump spout. The old man prepares for another jump, but finds he has competition – as a sweet young girl in her might garments seeks to jump out of the next window. The man leaps first, expecting to beat her to the ground. He does, but harder than expected, as the noble firefighters decide the rule of ladies first applies, and abandon the net, leaving the old geezer to carve a crater into the earth. The girl leaps, her bloomers blooming to provide a parachute effect to slow her fall, as Tom catches her in his arms, while Jerry fans her with his hat. The horse is at it for the third time, now having filled a whole barrel full of water. He tosses the water, barrel and all, at the building. The weakened structure collapses entirely upon the impact – and who emerges half-buried under the rubble but the disgruntled farmer. Looking around nervously for some way not to avoid taking the blame, the horse runs for the engine, and Tom and Jerry follow. In a nicely structured dimensional tracking shot up the street (perhaps Tashlin’s first piece of fancy camera work), the old man angrily pursues the engine. Suddenly, the detachable boiler is thrown from the engine, landing atop the old man to leave him staggering around the road blindly. Inside the spot where the boiler had been, we see Tom, Jerry, and the sweet young girl, cavorting atop the engine in a dance of ring-around-the-rosy, as the scene irises out.

The man struggles to regain a footing inside the house, running atop the water stream, climbing upon it hand-over-hand, etc., and finally gets back inside and over to the original window. Meanwhile, down below, the horse sets up a running gag, attempting to help with a small pail of water and a farm water pump. He fills a first pail, and prepares to throw it through a ground-floor window. However, a flame leaps out the window to toast the horse’s hoofs, causing him to waste the water on quenching his feet rather than extinguishing the main blaze. Back at the upper window, the old man nervously considers jumping, while Tom and Jerry position a fireman’s net below him. He jumps, but bounces off the trampoline surface up to the roof, and down the chimney, reappearing at the window in blackened form, to shout an Al Jolson, “Mammy”. The horse tries things again, but takes a burn to the tail, leading him to return to the water pimp just to soak his rear end under the pump spout. The old man prepares for another jump, but finds he has competition – as a sweet young girl in her might garments seeks to jump out of the next window. The man leaps first, expecting to beat her to the ground. He does, but harder than expected, as the noble firefighters decide the rule of ladies first applies, and abandon the net, leaving the old geezer to carve a crater into the earth. The girl leaps, her bloomers blooming to provide a parachute effect to slow her fall, as Tom catches her in his arms, while Jerry fans her with his hat. The horse is at it for the third time, now having filled a whole barrel full of water. He tosses the water, barrel and all, at the building. The weakened structure collapses entirely upon the impact – and who emerges half-buried under the rubble but the disgruntled farmer. Looking around nervously for some way not to avoid taking the blame, the horse runs for the engine, and Tom and Jerry follow. In a nicely structured dimensional tracking shot up the street (perhaps Tashlin’s first piece of fancy camera work), the old man angrily pursues the engine. Suddenly, the detachable boiler is thrown from the engine, landing atop the old man to leave him staggering around the road blindly. Inside the spot where the boiler had been, we see Tom, Jerry, and the sweet young girl, cavorting atop the engine in a dance of ring-around-the-rosy, as the scene irises out.

Warner Brothers would score a memorable hit in 1933 with an unusual gothic horror thriller, Mystery of the Wax Museum, filmed entirely in two-strop Technicolor. The film was the blueprint for Vincent Price’s later 3-D version, House of Wax, and was reputedly almost lost when the producers of the latter film attempted to have all memory of its predecessor eradicated by destroying prints or negatives. Fortunately, despite making the film difficult to access for decades, they did not succeed, and the superior original version has been preserved. Among the film’s most memorable moments is an early sequence where the curator’s gallery of masterpieces goes up in flames, thanks to a partner’s insistence on cashing in on insurance by means of arson. The imagery of the dissolving wax figures provided inspiration for two titles to be discussed in today’s article below. Whacks Museum (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Krazy Kat, 9/29/33 – Allen Rose/Preston Blair, anim.) finds Krazy as the curator of his own museum of marvels, with Kitty selling tickets outside. Krazy meticulously keeps things bright by dusting off his masterpieces, which amazingly have living, active lives of their own, even in the daytime without waiting for the mysterious stroke of midnight. He passes a reproduction of the statue of the Thinker, finding him engrossed in the national fad of the year that seemed to be lampooned by animated and live-action comedies from nearly every studio – a jigsaw puzzle. Only one key part of the puzzle has not been inserted – the face of a bathing beauty. Krazy locates the piece and inserts it – revealing that the shapely beauty has an ugly, goofy face. The Thinker comes to life, recoils at the image on the puzzle, ad makes a gesture of waving his hand in front of his nose as if to blow away a bad smell, uttering, “Phew”. A replica of the Statue of Liberty celebrates the repeal of prohibition, holding a full mug of beer in her upraised hand instead of a torch. A Joe E. Brown statue, seated with mouth open in a dentist’s chair, reacts with Brown’s traditional wide-moted, “Heyyyyyyy!”, when a fly enters his open mouth, and begins performing acrobatic flips from the uvula in his throat. A mother and child visiting the museum both have their fun, with the child sliding down the mile-long nose of a Jimmy Durante statue, and the mother switching cards among a table full of statues engaged in a poker game, to provide one player with a hand that converts to an image of a home bulging with wailing children at the windows – a “full house”. A statue of Mae West comes to life and performs a musical rendition of “Frankie and Johnnie”, then paraphrases West’s signature catch-phrase about “come up sometime” to a top-hatted gentleman statue nearby, who melts in heat of passion on the spot. The fires of love produce from his embers a fire for real, which quickly spreads across the gallery.

Warner Brothers would score a memorable hit in 1933 with an unusual gothic horror thriller, Mystery of the Wax Museum, filmed entirely in two-strop Technicolor. The film was the blueprint for Vincent Price’s later 3-D version, House of Wax, and was reputedly almost lost when the producers of the latter film attempted to have all memory of its predecessor eradicated by destroying prints or negatives. Fortunately, despite making the film difficult to access for decades, they did not succeed, and the superior original version has been preserved. Among the film’s most memorable moments is an early sequence where the curator’s gallery of masterpieces goes up in flames, thanks to a partner’s insistence on cashing in on insurance by means of arson. The imagery of the dissolving wax figures provided inspiration for two titles to be discussed in today’s article below. Whacks Museum (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Krazy Kat, 9/29/33 – Allen Rose/Preston Blair, anim.) finds Krazy as the curator of his own museum of marvels, with Kitty selling tickets outside. Krazy meticulously keeps things bright by dusting off his masterpieces, which amazingly have living, active lives of their own, even in the daytime without waiting for the mysterious stroke of midnight. He passes a reproduction of the statue of the Thinker, finding him engrossed in the national fad of the year that seemed to be lampooned by animated and live-action comedies from nearly every studio – a jigsaw puzzle. Only one key part of the puzzle has not been inserted – the face of a bathing beauty. Krazy locates the piece and inserts it – revealing that the shapely beauty has an ugly, goofy face. The Thinker comes to life, recoils at the image on the puzzle, ad makes a gesture of waving his hand in front of his nose as if to blow away a bad smell, uttering, “Phew”. A replica of the Statue of Liberty celebrates the repeal of prohibition, holding a full mug of beer in her upraised hand instead of a torch. A Joe E. Brown statue, seated with mouth open in a dentist’s chair, reacts with Brown’s traditional wide-moted, “Heyyyyyyy!”, when a fly enters his open mouth, and begins performing acrobatic flips from the uvula in his throat. A mother and child visiting the museum both have their fun, with the child sliding down the mile-long nose of a Jimmy Durante statue, and the mother switching cards among a table full of statues engaged in a poker game, to provide one player with a hand that converts to an image of a home bulging with wailing children at the windows – a “full house”. A statue of Mae West comes to life and performs a musical rendition of “Frankie and Johnnie”, then paraphrases West’s signature catch-phrase about “come up sometime” to a top-hatted gentleman statue nearby, who melts in heat of passion on the spot. The fires of love produce from his embers a fire for real, which quickly spreads across the gallery.

A line of flame climbs up the back of a statue of a circus performer holding a trapeze, and the fire forms into a little flame man who uses the trapeze to swing across the gallery, setting the trapeze ropes ablaze and allowing himself to reach to the other side of the room to further spread the inferno. The fire closes in on unsuspecting Krazy, who turns his attention from his dusting to react in shock, and beats a hasty retreat across the hall to keep one jump ahead of the heat. He encounters a sink on the wall, and diverts flow of water from the spout with his finger to aim it at the blaze. It has little effect, as the flame forms a mouth, and repeats the gag from Oswald’s “Going to Blazes” of ingesting, then spitting, the water back at Krazy. A clever sight-gag has Krazy open the water valve on a fire hose coiled on a spool, without unwinding the hose. The water emerges from the nozzle after a long trip, but curves in a spiral to match the looping of the hose before finally straightening out to take aim at the fire. Still, the fire grows in intensity. A nicely-composed dimensional shot has Krazy racing straight at the camera, screaming with fear, as the camera lens disappears into the blackness of his throat – then cut to the black on the back of his head for a reverse tail-away shot of him retreating with the flames in “hot pursuit”. Krazy finds pail with a lid atop, marked “Fire”. Assuming it is more water, he lifts the lid – only to find more flames inside. The flames begin to have an effect upon statues nearby. Four members of a chain gang receive a “goose” as the flames shoot between their legs. A statue of a fat female bather receives an ultra-fast diet plan by having pounds of wax melted off, reducing her to gorgeous proportions. The fire passes the poker player statues, melting ine player to remove his outfit and reduce him to a skeleton – upon the person of which are planted several extra concealed aces. A bust on an upper shelf dissolves, dripping down to the floor, where it amazingly cools and reforms into the identical shape from which it began. A statue of a full-grown dog is reduced to a pup. An armless Venus Di Milo has streams of wax melt and drip from her shoulders, then harden, producing her pair of missing arms. The fire proceeds along the nose of the Durante statue, prompting him to say before he completely dissolves, “Am I burnin’ up!” Thanks to a poorly-preserved soundtrack, the final curtain line, taken by a Greta Garbo statue as Krazy passes, seems to be inaudible – perhaps she is happy everyone is leaving, for the chance to be alone.

A line of flame climbs up the back of a statue of a circus performer holding a trapeze, and the fire forms into a little flame man who uses the trapeze to swing across the gallery, setting the trapeze ropes ablaze and allowing himself to reach to the other side of the room to further spread the inferno. The fire closes in on unsuspecting Krazy, who turns his attention from his dusting to react in shock, and beats a hasty retreat across the hall to keep one jump ahead of the heat. He encounters a sink on the wall, and diverts flow of water from the spout with his finger to aim it at the blaze. It has little effect, as the flame forms a mouth, and repeats the gag from Oswald’s “Going to Blazes” of ingesting, then spitting, the water back at Krazy. A clever sight-gag has Krazy open the water valve on a fire hose coiled on a spool, without unwinding the hose. The water emerges from the nozzle after a long trip, but curves in a spiral to match the looping of the hose before finally straightening out to take aim at the fire. Still, the fire grows in intensity. A nicely-composed dimensional shot has Krazy racing straight at the camera, screaming with fear, as the camera lens disappears into the blackness of his throat – then cut to the black on the back of his head for a reverse tail-away shot of him retreating with the flames in “hot pursuit”. Krazy finds pail with a lid atop, marked “Fire”. Assuming it is more water, he lifts the lid – only to find more flames inside. The flames begin to have an effect upon statues nearby. Four members of a chain gang receive a “goose” as the flames shoot between their legs. A statue of a fat female bather receives an ultra-fast diet plan by having pounds of wax melted off, reducing her to gorgeous proportions. The fire passes the poker player statues, melting ine player to remove his outfit and reduce him to a skeleton – upon the person of which are planted several extra concealed aces. A bust on an upper shelf dissolves, dripping down to the floor, where it amazingly cools and reforms into the identical shape from which it began. A statue of a full-grown dog is reduced to a pup. An armless Venus Di Milo has streams of wax melt and drip from her shoulders, then harden, producing her pair of missing arms. The fire proceeds along the nose of the Durante statue, prompting him to say before he completely dissolves, “Am I burnin’ up!” Thanks to a poorly-preserved soundtrack, the final curtain line, taken by a Greta Garbo statue as Krazy passes, seems to be inaudible – perhaps she is happy everyone is leaving, for the chance to be alone.

The Night Before Christmas (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony. 12/9/33 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.), receives honorable mention for inclusion among its many toys of a wind up pumper fire engine and a hook and ladder truck, complete with a working crew of firemen, who use the equipment to help decorate the Christmas tree. Employing a box of artificial snow, the firemen insert the feeder end of the hose in the box, then use the engine’s pumping mechanism to allow the other crew members on the hook and ladder to spray the snow from the nozzle end of the hose onto the limbs of the tree, providing a neat means of attaining the popular “flocking” effect pf icing along the tree branches.

Red Hot Mamma (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 2/2/34 – Dave Fleiscer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Dave Tendlar, anim.) has been comprehensively reviewed a few years back in these pages, as part of the “Go to Hades” series, as Betty, on a cold winter’s night, snuggles up by an open fire in the fireplace, and imagines herself entering the flames for a visit to the underworld of Hell. While flames of course abound throughout the cartoon, one particular sequence makes interesting use of fireman imagery. A chute is the entrance point for new arrivals into Hades, who are greeted by a pair of devils, who slip each lost soul into a fabric devil suit of light gray color, and zip them inside from the back. The souls are then transported to a large structure marked “Freshmen Hall”, and placed inside, while other devils ring a fire bell outside. A small hook and ladder truck with hose rolls to the scene, with three devil firemen aboard. They bring out the hose, and one of them takes aim at the hall – odd, as there is as yet no fire. But then, this is a different kind of “Fire” department, as the hose shoots flame instead of water, setting the building ablaze. From the engulfing flame, the new souls, now charred black to match the other devils around them, revel in the heat, and shout “Whoopee!” (The poor colorized version later produced of this film ruined the payoff of this gag, by omitting the animation of the charred new devils entirely.) A wonderfully creative and surreal entry in the Boop series, high within the rankings of its true classics.

Red Hot Mamma (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 2/2/34 – Dave Fleiscer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Dave Tendlar, anim.) has been comprehensively reviewed a few years back in these pages, as part of the “Go to Hades” series, as Betty, on a cold winter’s night, snuggles up by an open fire in the fireplace, and imagines herself entering the flames for a visit to the underworld of Hell. While flames of course abound throughout the cartoon, one particular sequence makes interesting use of fireman imagery. A chute is the entrance point for new arrivals into Hades, who are greeted by a pair of devils, who slip each lost soul into a fabric devil suit of light gray color, and zip them inside from the back. The souls are then transported to a large structure marked “Freshmen Hall”, and placed inside, while other devils ring a fire bell outside. A small hook and ladder truck with hose rolls to the scene, with three devil firemen aboard. They bring out the hose, and one of them takes aim at the hall – odd, as there is as yet no fire. But then, this is a different kind of “Fire” department, as the hose shoots flame instead of water, setting the building ablaze. From the engulfing flame, the new souls, now charred black to match the other devils around them, revel in the heat, and shout “Whoopee!” (The poor colorized version later produced of this film ruined the payoff of this gag, by omitting the animation of the charred new devils entirely.) A wonderfully creative and surreal entry in the Boop series, high within the rankings of its true classics.

If fire was a splashy-enough theme for Disney’s color premiere, then why not for Warner Brothers? This appears to have been the logic behind the planning for Honeymoon Hotel (Merrie Melodies (2-strip Cinecolor), 2/17/34, Earl Duvall, dir.), Warner’s first color cartoon. The film follows the romance and wedding of a ladybug and “tumble bug” in the community of Bugtown, into their wedding night at the hotel of the title’s name. The newlyweds are the center of attention at this swank, muti-story tower – in more ways than perhaps desirable – as the couple can’t’ seem to escape the curious gazes of the house detective, bellhops, maids, and even the man in the moon peering into their window. Only after considerable effort and turning out the room lights is the couple finally able to add a little spark to their life – a romantic flame, unseen by the camera, that raises the temperature of the wall thermometer to frightening levels, then sets off a fire alarm. Five engines roll out of the Bugtown fire department. (Inconsistently, only three turn up at the fire.) Designs of the three vehicles are clever. A seltzer bottle serves as a substitute for the boiler on the pumper engine. The hook and ladder is provided by a centipede carrying two fine tooth combs. And a unique escape ramp is provided by a vehicle whose chassis is a cheese grater, carrying an alarm clock for a fire bell, and a drill which is later raised to upper windows to provide a spiral slide to safety. For a fireman’s net, the crew catches leapers from the windows on a hot water bottle. Warner opts for the solid look for its flames, using a modification of Disney’s black and white technique by painting the flames in a near-white transparent paint (or accomplishing the same look with multiple exposures) without ink outlines around the fire. The choice may have been because of the two-strip process, and possible fear that a convincing yellow could not be obtained. (Actually, Ub Iwerks often proved that Cinecolor was fully capable of a good yellow, but Warner may have preferred not to take chances in its fledgling effort.) Whatever the reason, the result is more effective than the odd colors of Disney’s “Flowers and Trees”. Some pre-code humor slips in, with one bug gentleman and his female “partner” leaping from a window, with the male minus any trousers under his nightshirt. The pants leap out by themselves a few seconds later. Inside, the newlyweds race from door to door, finding flame at every exit. Their only safe haven is to jump into a Murphy bed, which folds into the wall. Suddenly, there is an explosion, and the hotel is nearly blasted apart, save for tha portion of the room where the Murphy bed is located. The bed falls open from the wall, revealing the couple. The fire seems to have gone out with the explosion, so the husband hangs a “Do Not Disturb” sign on the one surviving door (despite the fact that the remaining walls have been blasted away, so that the inside of the room can be seen from the street), and hops back into the Murphy bed with the wife. Again in pre-code fashion, realizing they are at last in bed together, the two bugs give a sly wink to the audience, and fold the bed back into the wall for a little privacy, however awkward. Hung on the bottom panel of the folding bed is a calendar, on which appears the picture of an infant bug. The photo also winks at the camera, signaling that someone will be expecting soon, for the fade out.

If fire was a splashy-enough theme for Disney’s color premiere, then why not for Warner Brothers? This appears to have been the logic behind the planning for Honeymoon Hotel (Merrie Melodies (2-strip Cinecolor), 2/17/34, Earl Duvall, dir.), Warner’s first color cartoon. The film follows the romance and wedding of a ladybug and “tumble bug” in the community of Bugtown, into their wedding night at the hotel of the title’s name. The newlyweds are the center of attention at this swank, muti-story tower – in more ways than perhaps desirable – as the couple can’t’ seem to escape the curious gazes of the house detective, bellhops, maids, and even the man in the moon peering into their window. Only after considerable effort and turning out the room lights is the couple finally able to add a little spark to their life – a romantic flame, unseen by the camera, that raises the temperature of the wall thermometer to frightening levels, then sets off a fire alarm. Five engines roll out of the Bugtown fire department. (Inconsistently, only three turn up at the fire.) Designs of the three vehicles are clever. A seltzer bottle serves as a substitute for the boiler on the pumper engine. The hook and ladder is provided by a centipede carrying two fine tooth combs. And a unique escape ramp is provided by a vehicle whose chassis is a cheese grater, carrying an alarm clock for a fire bell, and a drill which is later raised to upper windows to provide a spiral slide to safety. For a fireman’s net, the crew catches leapers from the windows on a hot water bottle. Warner opts for the solid look for its flames, using a modification of Disney’s black and white technique by painting the flames in a near-white transparent paint (or accomplishing the same look with multiple exposures) without ink outlines around the fire. The choice may have been because of the two-strip process, and possible fear that a convincing yellow could not be obtained. (Actually, Ub Iwerks often proved that Cinecolor was fully capable of a good yellow, but Warner may have preferred not to take chances in its fledgling effort.) Whatever the reason, the result is more effective than the odd colors of Disney’s “Flowers and Trees”. Some pre-code humor slips in, with one bug gentleman and his female “partner” leaping from a window, with the male minus any trousers under his nightshirt. The pants leap out by themselves a few seconds later. Inside, the newlyweds race from door to door, finding flame at every exit. Their only safe haven is to jump into a Murphy bed, which folds into the wall. Suddenly, there is an explosion, and the hotel is nearly blasted apart, save for tha portion of the room where the Murphy bed is located. The bed falls open from the wall, revealing the couple. The fire seems to have gone out with the explosion, so the husband hangs a “Do Not Disturb” sign on the one surviving door (despite the fact that the remaining walls have been blasted away, so that the inside of the room can be seen from the street), and hops back into the Murphy bed with the wife. Again in pre-code fashion, realizing they are at last in bed together, the two bugs give a sly wink to the audience, and fold the bed back into the wall for a little privacy, however awkward. Hung on the bottom panel of the folding bed is a calendar, on which appears the picture of an infant bug. The photo also winks at the camera, signaling that someone will be expecting soon, for the fade out.

Oswald Rabbit’s Wax Works (Lantz/Universal, 6/25/34 – Walter Lantz, dir.), attempts to follow in the footsteps of Krazy Kat’s mini-epic described above, again capitalizing off “Mystery of the Wax Museum”, though a trifle late in its timing. Its use of fire is much more brief and oblique, but again merits honorable mention. On a stormy night, Oswald receives a bundle on the doorstep of his museum, with an abandoned waif needing caring for. In an unusually baritone voice, Oswald grumbles that they can’t make a fool out of him by dumping an infant into his lap, and is about to cast the kid outside, until the severity of the storm softens his heart, and he invites the kid back in. “Swell joint ya got here”, remarks the kid, as Oswald leads him through the museum hall to an upstairs apartment above the museum, where Oswald shares his bed with the child for the night. In the wee small hours, the kid goes downstairs for a drink of water, then starts snooping around the museum displays. The waif’s drop seat of his pajamas has fallen open (though we did not see him utilize the rest room for such purpose), and he approaches one of the statues with the request that someone “button him”. Unfortunately, the first statue he asks is Venus Di Milo, who gestures with her shoulders her inability to help him for lack of arms. The Thinker provides the necessary buttoning. Then the waif asks, “What’cha thinking about?” The statue replies he is thinking about everyone having fun, and invites the statues around him to wake up and join him. Nero stomps out a beat, and begins with a violin solo. Romeo and Juliet perform the balcony scene in an operatic mode, though disrupted by Groucho Marx, who takes the girl for himself, and (in a terrible impression sounding nothing like him), quips, “Not tonight, Romeo.” Sally Rand (wearing underwear) performs a fan dance, while the waif comments that she’s got rhythm, and the Thinker adds, “Yowsaa!” Napoleon wanders after Sally, but is again intercepted by Groucho’s “Not tonight, Josephine”, causing Napoleon to deck Groucho and knock him cold.

Oswald Rabbit’s Wax Works (Lantz/Universal, 6/25/34 – Walter Lantz, dir.), attempts to follow in the footsteps of Krazy Kat’s mini-epic described above, again capitalizing off “Mystery of the Wax Museum”, though a trifle late in its timing. Its use of fire is much more brief and oblique, but again merits honorable mention. On a stormy night, Oswald receives a bundle on the doorstep of his museum, with an abandoned waif needing caring for. In an unusually baritone voice, Oswald grumbles that they can’t make a fool out of him by dumping an infant into his lap, and is about to cast the kid outside, until the severity of the storm softens his heart, and he invites the kid back in. “Swell joint ya got here”, remarks the kid, as Oswald leads him through the museum hall to an upstairs apartment above the museum, where Oswald shares his bed with the child for the night. In the wee small hours, the kid goes downstairs for a drink of water, then starts snooping around the museum displays. The waif’s drop seat of his pajamas has fallen open (though we did not see him utilize the rest room for such purpose), and he approaches one of the statues with the request that someone “button him”. Unfortunately, the first statue he asks is Venus Di Milo, who gestures with her shoulders her inability to help him for lack of arms. The Thinker provides the necessary buttoning. Then the waif asks, “What’cha thinking about?” The statue replies he is thinking about everyone having fun, and invites the statues around him to wake up and join him. Nero stomps out a beat, and begins with a violin solo. Romeo and Juliet perform the balcony scene in an operatic mode, though disrupted by Groucho Marx, who takes the girl for himself, and (in a terrible impression sounding nothing like him), quips, “Not tonight, Romeo.” Sally Rand (wearing underwear) performs a fan dance, while the waif comments that she’s got rhythm, and the Thinker adds, “Yowsaa!” Napoleon wanders after Sally, but is again intercepted by Groucho’s “Not tonight, Josephine”, causing Napoleon to deck Groucho and knock him cold.

But the real fun is yet to come. The waif ventures too near a door to the “Chamber of Horrors”, and is pulled inside by a hairy hand. The appendage belongs to the Hunchback of Notre Dame, who introduces a rogue’s gallery of villains, including probably the earliest assembly in cartoons of the classic Universal monsters – Dracula, Frankenstein, the Mummy, and the Invisible Man (who wears a few garments suspended on nothing, so we can keep track of where he is). For good measure, Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde also makes an appearance, giving a nod to Paramount’s horror hit of a few years back, as well as Bluebeard. The waif snaps a stocking garter on the Invisible Man’s ankle, and makes a break for it, causing Mr. Invisible to rally the others to “Get him, boys.” The waif runs, a step ahead of the sinister clutching hands, and collides with a work table, upon which is a lit candle and a blow torch. The candle is knocked over, lighting the torch flame. Bluebeard approaches, but the boy turns the fire upon him, melting him into a pile of goo. The other monsters shudder in horror, and turn tail, as the boy pursues them with the flame. They pile up against a closed door, and form into a dog pile of scrambling limbs, resulting in an odd configuration where they are all spinning like the steps of a wheel, with the Mummy in the middle playing the role of a running hamster. The boy keeps the flame upon them, but they do not get enough of it to dissolve, because the Invisible Man creeps up behind the boy, and yanks the torch away, also grabbing up the boy by his pajama collar. Invisible has plans for the boy, mirroring the intentions of the mad wax works operator in Warner’s feature – to dip the boy in boiling wax, and make him a statue. As the fiend tips a pot of the stuff to pour upon the boy, the camera cuts to Oswald’s bedroom, as a scream is heard offscreen. Oswald races to the source of the sound, to find the boy fully coated, and indeed turned into a statue! (It would sem quite doubtful that the Hays Office would have ever approved such a shot after code enforcement went into effect – the murder of a little boy would presumably have been considered much too horrific. The Invisible Man appears again, and announces that Oswald will be next. Oswald is manacled to a table, and the Invisible Man again holds a container of the boiling goo above him to drop down upon his head. As Oswald struggles, the scene dissolves back to Oswald’s bedroom, where it turns out Oswald is dreaming, but a very similar situation is about to happen for real. The little boy holds a dripping wax candle over Oswald’s head, and the hot wax gives Oswald a mild burn on the forehead, sending him screaming and leaping into the air. The boy laughs at causing Oswald such a fright, then turns around to reveal his pajama drop seat is open again, and asks, “Button me up.”

But the real fun is yet to come. The waif ventures too near a door to the “Chamber of Horrors”, and is pulled inside by a hairy hand. The appendage belongs to the Hunchback of Notre Dame, who introduces a rogue’s gallery of villains, including probably the earliest assembly in cartoons of the classic Universal monsters – Dracula, Frankenstein, the Mummy, and the Invisible Man (who wears a few garments suspended on nothing, so we can keep track of where he is). For good measure, Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde also makes an appearance, giving a nod to Paramount’s horror hit of a few years back, as well as Bluebeard. The waif snaps a stocking garter on the Invisible Man’s ankle, and makes a break for it, causing Mr. Invisible to rally the others to “Get him, boys.” The waif runs, a step ahead of the sinister clutching hands, and collides with a work table, upon which is a lit candle and a blow torch. The candle is knocked over, lighting the torch flame. Bluebeard approaches, but the boy turns the fire upon him, melting him into a pile of goo. The other monsters shudder in horror, and turn tail, as the boy pursues them with the flame. They pile up against a closed door, and form into a dog pile of scrambling limbs, resulting in an odd configuration where they are all spinning like the steps of a wheel, with the Mummy in the middle playing the role of a running hamster. The boy keeps the flame upon them, but they do not get enough of it to dissolve, because the Invisible Man creeps up behind the boy, and yanks the torch away, also grabbing up the boy by his pajama collar. Invisible has plans for the boy, mirroring the intentions of the mad wax works operator in Warner’s feature – to dip the boy in boiling wax, and make him a statue. As the fiend tips a pot of the stuff to pour upon the boy, the camera cuts to Oswald’s bedroom, as a scream is heard offscreen. Oswald races to the source of the sound, to find the boy fully coated, and indeed turned into a statue! (It would sem quite doubtful that the Hays Office would have ever approved such a shot after code enforcement went into effect – the murder of a little boy would presumably have been considered much too horrific. The Invisible Man appears again, and announces that Oswald will be next. Oswald is manacled to a table, and the Invisible Man again holds a container of the boiling goo above him to drop down upon his head. As Oswald struggles, the scene dissolves back to Oswald’s bedroom, where it turns out Oswald is dreaming, but a very similar situation is about to happen for real. The little boy holds a dripping wax candle over Oswald’s head, and the hot wax gives Oswald a mild burn on the forehead, sending him screaming and leaping into the air. The boy laughs at causing Oswald such a fright, then turns around to reveal his pajama drop seat is open again, and asks, “Button me up.”

The Parrotville Fire Department (Van Buren, RKO, Rainbow Parade (2 strip Technicolor), 8/16/34 – Burt Gillett/Steve Muffati, dir.), is the first of a fanciful three-episode jaunt into the rural community of Parrotville – populated, of course, entirely by parrots (of the pet store variety, as opposed to wild jungle birds). The film scores more from rich character animation than from its gag material, attempting a “slice of life” atmosphere that prevails through the limited series. Though not ywet referred to by name, we are introduced to an old parrot later known as “The Skipper”, in charge of the volunteer brigade. He brags to the audience about his record, including a recent fire they put out in record time – even though the house burned down. He admits of himself to being slow climbing ladders – but all the faster coming down them. He polishes away at their motorized pumper truck – perhaps a little too hard, as the headlights keep getting knocked off. The other members of the brigade, occupying their time in a four-handed game of poker (using perches instead of seats around the table), laugh with hilarity at these mishaps, but Skipper assures them “There’s many a fire left in ol’ Betsy”. The engine responds to his kind words, developing a face and licking the Skipper like a trained pup. The poker game continues, with one player ditching his entire hand into a spittoon, substituting another for it from a hidden pocket of his trousers. Bidding increases in stacks of cookies and soda crackers, until the bet is called and hands revealed. Everyone is holding five aces! The table erupts in a fisticuffs brawl, until an alarm bell is heard. Skipper and one assistant roll out of the station on Betsy, while the remaining firebirds report to a long hose truck, containing a chassis full of perches for each of them. At the fire scene, after some routine problems in getting the hose hooked up and the water turned on, the flame in the building’s windows breaks into a legion of small flame-men, each shaped like the flickering light from the wick of a candle, and decide to cavort on the ground instead of wasting time with the uninteresting building. Their design is surprisingly familiar if you’re a Disney fan, as they look virtually identical to those used a year later in the classic “Mickey’s Fire Brigade”. In fact, scenes of the parrots’ first reactions to them also look like they stepped right out of the later, better known cartoon, as parrots swat at the flame men with brooms in attempt to smother them, or cut them with axes which only dissect them, in the same manner as Flip the Frog’s “Fire-Fire” – activities which would appear again in the later Mickey cartoon. A good deal of chasing takes place with no real standout gags, and the birds ultimately pile onto old Betsy and beat a retreat back to the fire station, as the flame-men pursue them like a regiment down the street. The parrots drive Betsy through the station’s front door, then retreat out a rear door, shutting it behind them. The flames enter at the front, and the parrots race around and close the front door, locking the flames inside. Though the flames have custody of the station, the parrots shake each other’s hands, classifying the fire as 100% contained. Well, not exactly, as a bell is heard from the station’s rooftop tower. The flames have broken through the roof, and are playfully tugging away at the station’s bell cords, while other flames begin burning the edges of the station roof. Who’s in control of who? The parrots watch helplessly and run around in circles below, while the fire continues to have its field day in the station rafters, for the iris out.

The Parrotville Fire Department (Van Buren, RKO, Rainbow Parade (2 strip Technicolor), 8/16/34 – Burt Gillett/Steve Muffati, dir.), is the first of a fanciful three-episode jaunt into the rural community of Parrotville – populated, of course, entirely by parrots (of the pet store variety, as opposed to wild jungle birds). The film scores more from rich character animation than from its gag material, attempting a “slice of life” atmosphere that prevails through the limited series. Though not ywet referred to by name, we are introduced to an old parrot later known as “The Skipper”, in charge of the volunteer brigade. He brags to the audience about his record, including a recent fire they put out in record time – even though the house burned down. He admits of himself to being slow climbing ladders – but all the faster coming down them. He polishes away at their motorized pumper truck – perhaps a little too hard, as the headlights keep getting knocked off. The other members of the brigade, occupying their time in a four-handed game of poker (using perches instead of seats around the table), laugh with hilarity at these mishaps, but Skipper assures them “There’s many a fire left in ol’ Betsy”. The engine responds to his kind words, developing a face and licking the Skipper like a trained pup. The poker game continues, with one player ditching his entire hand into a spittoon, substituting another for it from a hidden pocket of his trousers. Bidding increases in stacks of cookies and soda crackers, until the bet is called and hands revealed. Everyone is holding five aces! The table erupts in a fisticuffs brawl, until an alarm bell is heard. Skipper and one assistant roll out of the station on Betsy, while the remaining firebirds report to a long hose truck, containing a chassis full of perches for each of them. At the fire scene, after some routine problems in getting the hose hooked up and the water turned on, the flame in the building’s windows breaks into a legion of small flame-men, each shaped like the flickering light from the wick of a candle, and decide to cavort on the ground instead of wasting time with the uninteresting building. Their design is surprisingly familiar if you’re a Disney fan, as they look virtually identical to those used a year later in the classic “Mickey’s Fire Brigade”. In fact, scenes of the parrots’ first reactions to them also look like they stepped right out of the later, better known cartoon, as parrots swat at the flame men with brooms in attempt to smother them, or cut them with axes which only dissect them, in the same manner as Flip the Frog’s “Fire-Fire” – activities which would appear again in the later Mickey cartoon. A good deal of chasing takes place with no real standout gags, and the birds ultimately pile onto old Betsy and beat a retreat back to the fire station, as the flame-men pursue them like a regiment down the street. The parrots drive Betsy through the station’s front door, then retreat out a rear door, shutting it behind them. The flames enter at the front, and the parrots race around and close the front door, locking the flames inside. Though the flames have custody of the station, the parrots shake each other’s hands, classifying the fire as 100% contained. Well, not exactly, as a bell is heard from the station’s rooftop tower. The flames have broken through the roof, and are playfully tugging away at the station’s bell cords, while other flames begin burning the edges of the station roof. Who’s in control of who? The parrots watch helplessly and run around in circles below, while the fire continues to have its field day in the station rafters, for the iris out.

Popeye and Bluto have at it, as sole proprietors of rival fire companies, in The Two-Alarm Fire (Fleischer/Paramount, 10/26/34 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Nicholas Tafuri, anim.). The boys’ respective volunteer fire companies, consisting only of themselves and a hook and ladder truck they have to pull themselves without the aid of a horse, share one fire house, divided neatly down the middle. Probably never expecting to both be called on the same job, the two exchange rhyming boasts about their abilities to put out trouble, and in traditional fashion aggravate each other by interfering with each other’s work. Bluto squirts fire extinguisher solution all over Popeye’s newly-polished truck, while Popeye takes the spool of the hose winder from his vehicle, blows into the end of the hose nozzle, and clobbers Bluto with the unwinding hose and spool, like a giant birthday party favor. In another part of town, from causes unknown, a room of Olive Oyl’s three-story house catches fire, flames emerging from the window. Olive begins screaming for help from the next room, until the flames join her by spreading to the same window. Olive travels to every window of the place, the flame in each instance meeting her there a second later. When there are no more windows, Olive pops out a hatch in the roof, with the fire still right behind her, leaving her stranded on the rooftop. A flame-man divides off from the rest of the activity, slips out of the house from under the front door, and conscientiously climbs up a pole to a fire box, to turn in a report about itself. (Tex Avery would remember this gag for reuse over a decade later in “Red Hot Rangers”, though his flame had more personality, and was likely making the report just to have sheer fun frustrating the rangers, rather than out of any pangs of civic-mindedness.) The side-by-side alarm bells in the fire station go off, alerting both companies that help is needed. (The alarm bells develop faces, and disdainfully grimace at each other, their clappers positioned as if holding hands in front of their nose to give each other a razz.) Popeye and Bluto engage in a long-distance foot race to tow their engines to the site of the danger, where te flames in each window form into the shape of extended arms, each shaking the hand of the fire in the next window, to congratulate each other on a mission well-accomplished.

Popeye and Bluto have at it, as sole proprietors of rival fire companies, in The Two-Alarm Fire (Fleischer/Paramount, 10/26/34 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Nicholas Tafuri, anim.). The boys’ respective volunteer fire companies, consisting only of themselves and a hook and ladder truck they have to pull themselves without the aid of a horse, share one fire house, divided neatly down the middle. Probably never expecting to both be called on the same job, the two exchange rhyming boasts about their abilities to put out trouble, and in traditional fashion aggravate each other by interfering with each other’s work. Bluto squirts fire extinguisher solution all over Popeye’s newly-polished truck, while Popeye takes the spool of the hose winder from his vehicle, blows into the end of the hose nozzle, and clobbers Bluto with the unwinding hose and spool, like a giant birthday party favor. In another part of town, from causes unknown, a room of Olive Oyl’s three-story house catches fire, flames emerging from the window. Olive begins screaming for help from the next room, until the flames join her by spreading to the same window. Olive travels to every window of the place, the flame in each instance meeting her there a second later. When there are no more windows, Olive pops out a hatch in the roof, with the fire still right behind her, leaving her stranded on the rooftop. A flame-man divides off from the rest of the activity, slips out of the house from under the front door, and conscientiously climbs up a pole to a fire box, to turn in a report about itself. (Tex Avery would remember this gag for reuse over a decade later in “Red Hot Rangers”, though his flame had more personality, and was likely making the report just to have sheer fun frustrating the rangers, rather than out of any pangs of civic-mindedness.) The side-by-side alarm bells in the fire station go off, alerting both companies that help is needed. (The alarm bells develop faces, and disdainfully grimace at each other, their clappers positioned as if holding hands in front of their nose to give each other a razz.) Popeye and Bluto engage in a long-distance foot race to tow their engines to the site of the danger, where te flames in each window form into the shape of extended arms, each shaking the hand of the fire in the next window, to congratulate each other on a mission well-accomplished.

Bluto hooks up his hose to a hydrant with brute force, uprooting the hydrant from the water pipe to twist it onto the hose connection, then slamming the hydrant back down of the pipe to get it operational. Popeye gracefully flings his hose in an arc off the winding spool, launching one end of it across the street, to self-twist its connector onto a second hydrant. (The method has one unexplained drawback – no one appears to go across the street to actually turn the hydrant on, so where’s the water coming from?) Bluto takes aim at various windows with his hose, as a large flame dodges from one window to another, then divides to stick its head out two windows on opposite sides of the building. Despite the hose’s high water pressure which should make the stunt impossible, Bluto places one finger into the center of the hose’s water flow, and divides the jet of water in two to attach both flames simultaneously. Popeye spots a row of small flames traveling in a row from one side of the house to the other, visible where a wooden slat has fallen away close to the roof. The effect is that of a shooting gallery (with the flames assuming the shape of ducks in the middle of the sequence), and Popeye reacts accordingly, by folding and unfolding his hose to take intermittent shots at each flame, knocking them down one by one. To add to the effect, although the shots are totally unnecessary to fighting the fire, a weather vane becomes partially unbolted, and dangles below the roof eaves, swinging back and forth as a moving target for Popeye to score extra points upon, each hit producing a metallic clang like a gallery score bell. Now Bluto deviates from his job, and begins to “play” with Popeye, turning his hose upon the sailor. Popeye stands his ground, and turns his own hose directly at Bluto’s. Though the two streams of water should be exactly equal; coming from the same public water system, a pish-of-war contest commences between the respective streams of water, Popeye’s eventually winning to douse Bluto. The boys now, for the first time, become aware of Olive’s screams from the roof. “I’ll be right up. Keep cool”, yells Popeye. The sailor “compresses” a wooden ladder as if it were rubber, then releases it, causing it to spring upwards and hook onto the edge of the roof. Popeye climbs, nearly reaching the top. Except jealous Bluto turns the fire hose upon him again, twice in a row, knocking him back to the ground. “You done that accidentally on purpose”, protests Popeye.

Bluto hooks up his hose to a hydrant with brute force, uprooting the hydrant from the water pipe to twist it onto the hose connection, then slamming the hydrant back down of the pipe to get it operational. Popeye gracefully flings his hose in an arc off the winding spool, launching one end of it across the street, to self-twist its connector onto a second hydrant. (The method has one unexplained drawback – no one appears to go across the street to actually turn the hydrant on, so where’s the water coming from?) Bluto takes aim at various windows with his hose, as a large flame dodges from one window to another, then divides to stick its head out two windows on opposite sides of the building. Despite the hose’s high water pressure which should make the stunt impossible, Bluto places one finger into the center of the hose’s water flow, and divides the jet of water in two to attach both flames simultaneously. Popeye spots a row of small flames traveling in a row from one side of the house to the other, visible where a wooden slat has fallen away close to the roof. The effect is that of a shooting gallery (with the flames assuming the shape of ducks in the middle of the sequence), and Popeye reacts accordingly, by folding and unfolding his hose to take intermittent shots at each flame, knocking them down one by one. To add to the effect, although the shots are totally unnecessary to fighting the fire, a weather vane becomes partially unbolted, and dangles below the roof eaves, swinging back and forth as a moving target for Popeye to score extra points upon, each hit producing a metallic clang like a gallery score bell. Now Bluto deviates from his job, and begins to “play” with Popeye, turning his hose upon the sailor. Popeye stands his ground, and turns his own hose directly at Bluto’s. Though the two streams of water should be exactly equal; coming from the same public water system, a pish-of-war contest commences between the respective streams of water, Popeye’s eventually winning to douse Bluto. The boys now, for the first time, become aware of Olive’s screams from the roof. “I’ll be right up. Keep cool”, yells Popeye. The sailor “compresses” a wooden ladder as if it were rubber, then releases it, causing it to spring upwards and hook onto the edge of the roof. Popeye climbs, nearly reaching the top. Except jealous Bluto turns the fire hose upon him again, twice in a row, knocking him back to the ground. “You done that accidentally on purpose”, protests Popeye.

Before Popeye can retaliate, Bluto hits him with the water again, spinning him around dizzily, then clobbers the sailor with the hose nozzle while he is still groggy. Now Bluto decides to claim hero rights himself, leaning his own ladder against the building to climb up. He fails to notice the flames igniting the upright poles of the ladder behind him, so that, as Bluto climbs, the lower portions of the ladder are incinerated behind him. When he arrives on the roof, he finds himself a prisoner too, with no means of climbing down, Suddenly, a wall of flame breaks its way through the roof top in terrifying fashion, completely obscuring Bluto and Olive from view, leaving us guessing as to their fate. Time for Popeye’s spinach. Without a ladder, he hops from windowsill to windowsill up to the rooftop. Reaching the wall of flame, he parts it with his hands as if it were a curtain, retrieving the fainted Olive and Bluto from the other side. The remainder of the roof collapses out from under him, but Popeye walks through the inferno unharmed, carrying the fallen victims to safety upon the front lawn. Reviving Olive first, and assured of her safety, Popeye turns his attention to Bluto, forcing inhaled smoke out of Bluto’s abdomen, until Bluto is able to stand in wobbly fashion. Popeye asks if he is all right, and when Bluto nods yes, replies, “That’s fine” – then socks Bluto in the jaw, leaving him out like a light again. “Popeye, my house”, shouts Olive. Popeye takes a deep inhale, and blows like a windstorm at the house. The fire is cleanly swept away – although little is left of the structure but charred floors and chimney smokestack. No one seems to be upset at this development (maybe Olive has paid her insurance premium), and Popeye closes, arm in arm with Olive, with his signature song and pipe toot.

Before Popeye can retaliate, Bluto hits him with the water again, spinning him around dizzily, then clobbers the sailor with the hose nozzle while he is still groggy. Now Bluto decides to claim hero rights himself, leaning his own ladder against the building to climb up. He fails to notice the flames igniting the upright poles of the ladder behind him, so that, as Bluto climbs, the lower portions of the ladder are incinerated behind him. When he arrives on the roof, he finds himself a prisoner too, with no means of climbing down, Suddenly, a wall of flame breaks its way through the roof top in terrifying fashion, completely obscuring Bluto and Olive from view, leaving us guessing as to their fate. Time for Popeye’s spinach. Without a ladder, he hops from windowsill to windowsill up to the rooftop. Reaching the wall of flame, he parts it with his hands as if it were a curtain, retrieving the fainted Olive and Bluto from the other side. The remainder of the roof collapses out from under him, but Popeye walks through the inferno unharmed, carrying the fallen victims to safety upon the front lawn. Reviving Olive first, and assured of her safety, Popeye turns his attention to Bluto, forcing inhaled smoke out of Bluto’s abdomen, until Bluto is able to stand in wobbly fashion. Popeye asks if he is all right, and when Bluto nods yes, replies, “That’s fine” – then socks Bluto in the jaw, leaving him out like a light again. “Popeye, my house”, shouts Olive. Popeye takes a deep inhale, and blows like a windstorm at the house. The fire is cleanly swept away – although little is left of the structure but charred floors and chimney smokestack. No one seems to be upset at this development (maybe Olive has paid her insurance premium), and Popeye closes, arm in arm with Olive, with his signature song and pipe toot.

As a famous old march stated it, we’ll “Blaze Away” some more, next time.