Reading the bones of the dead: the painstaking, painful process of returning genocide victims to their families

“Who would like to share their testimonio with the North American anthropologist?” a local woman asks a room full of men, women and children, survivors of genocide in Guatemala.

Testimonio is a ritual for the collective telling and sharing of stories of violence and loss. Alexa Hagerty, a US anthropologist who was present in the room, did not see this coming. She had spent months training with forensic teams in exhumation at mass grave sites, investigating human rights violations in Guatemala and Argentina, countries ravaged by dictatorships and genocide.

Review: Still Life with Bones: Genocide, Forensics and What Remains – Alexa Hagerty (Penguin Random House)

In this room, in the El Quiché region, in 2014, a local woman gestured to her to take a seat and to listen to testimonios. Hagerty did as she was told, but felt as though she was intruding in other people’s lives and their pain. She wondered if she was doing more harm than good by hearing stories of systemic persecution, of massacres, torture, rape, murdered children and pregnant women, destroyed villages and scorched fields.

Hagerty knows that “taking the lid off sadness” could be retraumatising and will not necessarily bring meaningful change into the storytellers’ lives. It will not suddenly lift them from poverty or help them find peace. She “was slowly learning” that “the fieldwork” in Guatemala did not mean doing “one on one interviews” in a private setting. Instead, she found herself listening to “the soup pot of testimonio”; a chorus of “silence and words” from the abyss of grief and loss.

One of the longest armed conflicts in Latin America, the Guatemalan Civil War raged from 1960 to 1996 (when a peace accord was signed). Of almost 200,000 people who were killed or forcibly “disappeared”, 83% of victims were indigenous. Some 93% of civilian executions were carried out by government forces.

Similarly, in Argentina, 30,000 people were forcibly disappeared between 1976 and 1983. They are the desaparecidos Hagerty and teams of forensic anthropologists have been trying to uncover in their “work against impunity and forgetting”.

The remains of thousands of Guatemalan and Argentinian women, men and children were buried in unmarked mass graves. It is a “painstakingly slow” job to “remove the dead from where they must not be” and piece together the “jigsaw puzzle” of exhumed bones.

More years are then needed to prove the victims’ identity – bones need to match DNA tests taken from their families. Only then are they returned to them. For forensic anthropologists, “working fast is imperative”, so the bones are returned while the families of the killed are “still alive to mourn and bury them”. Until then, the lives of these families are suspended as they wait for the dead to regain their names.

Hagerty’s book, Still Life with Bones, is a voyage into the brutality of the genocide that took place in Guatemala, and in Argentina’s “Dirty War”. It is also about the bureaucratic violence of state institutions, unfolding in the aftermath.

“Justice is expensive”, she writes; many families cannot afford to travel for DNA tests, even if the tests themselves are free. Victims’ families need a day’s wages to take a bus to the capital of Guatemala to file papers, attend a hearing, or get a cheek swab. Many cannot afford this, so matching is delayed, return of bones is delayed, and proper burial has to wait.

A government bureaucrat needs to sign the paperwork to “release the bodies”. Hagerty describes the maltreatment of poor indigenous families waiting to collect bones of their loved ones in Guatemalan governmental offices.

Today, Guatemala is not at war, yet Guatemala City remains one of the most violent places in the world. More than 80% of its indigenous population lives in poverty. People still live in terror. Hagerty writes: “victims and perpetrators still live side by side in many Guatemalan cities” – something that is common to most postwar and post-genocidal communities. They are “intimate enemies” – former friends and neighbours now trying to rebuild their lives together.

During and after Guatemala’s civil war, human rights activists have been executed for speaking up, she writes. On September 11 1990, anthropologist Myrna Mack was stabbed to death, or in legal terms “arbitrarily deprived of life”, by state military agents. On March 7 2023 it was reported that three human rights defenders and one journalist were killed in Guatemala. On March 31, another journalist was shot dead.

Read more: Guatemala: 25 years later, 'firm and lasting peace' is nowhere to be found

Reburying ‘with a ritual and a name’

Hagerty holds a PhD in anthropology from Stanford University and is an affiliate at the University of Cambridge. She trained in forensic anthropology, a sub-field of physical anthropology and the study of human skeletal remains; it uses techniques of archaeology to solve national and international criminal cases.

Hagerty tells us that “bones and texts are the same”; they can be both “articulated and read”. Oral histories give humanity to bones and help narrate a life. “Both words and bones must be arranged in the right order for their meaning to be clear.”

The lands in Guatemala and Argentina are soaked with bones of the dead, often victims of “enforced disappearance”, a crime against humanity only recently added officially to the plethora of international crimes.

This crime has been widely practised in many countries, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chile, Cambodia and most recently Ukraine, to name a few. The bones unearthed, seen and touched by Hagerty, haunt her in dreams and during her travels to other excavation sites. The sensitive research she performs carries the risk of personal harm, and she does not shy away from telling us how her work has imprinted scars on her mind and body.

Read more: Moral ambiguity and the representation of genocide – is there a limit to what can be depicted?

Death is also “a booming business” for coffin makers, funeral homes and flower sellers. In a dire economy, the dead feed the living. Guatemala is a country where cemeteries run out of spaces. Failure to pay for the grave results in removal of the dead - their bones wrapped in a plastic bag and discarded with others in “a deep dry well of bones”. The rest – clothing, flowers and the coffin – is tossed into landfill.

Still, while hiding the traumatised dead, the earth also gives birth to minerals, water and plants. In Sarajevo, photographer Azem Kurtic recently held an exhibition of photographs of mass grave locations scattered across Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Kurtic realised “a deceased human body takes on another life as it nurtures grass and other plants.” Life and death intertwine under the ground where the “past and present converge”.

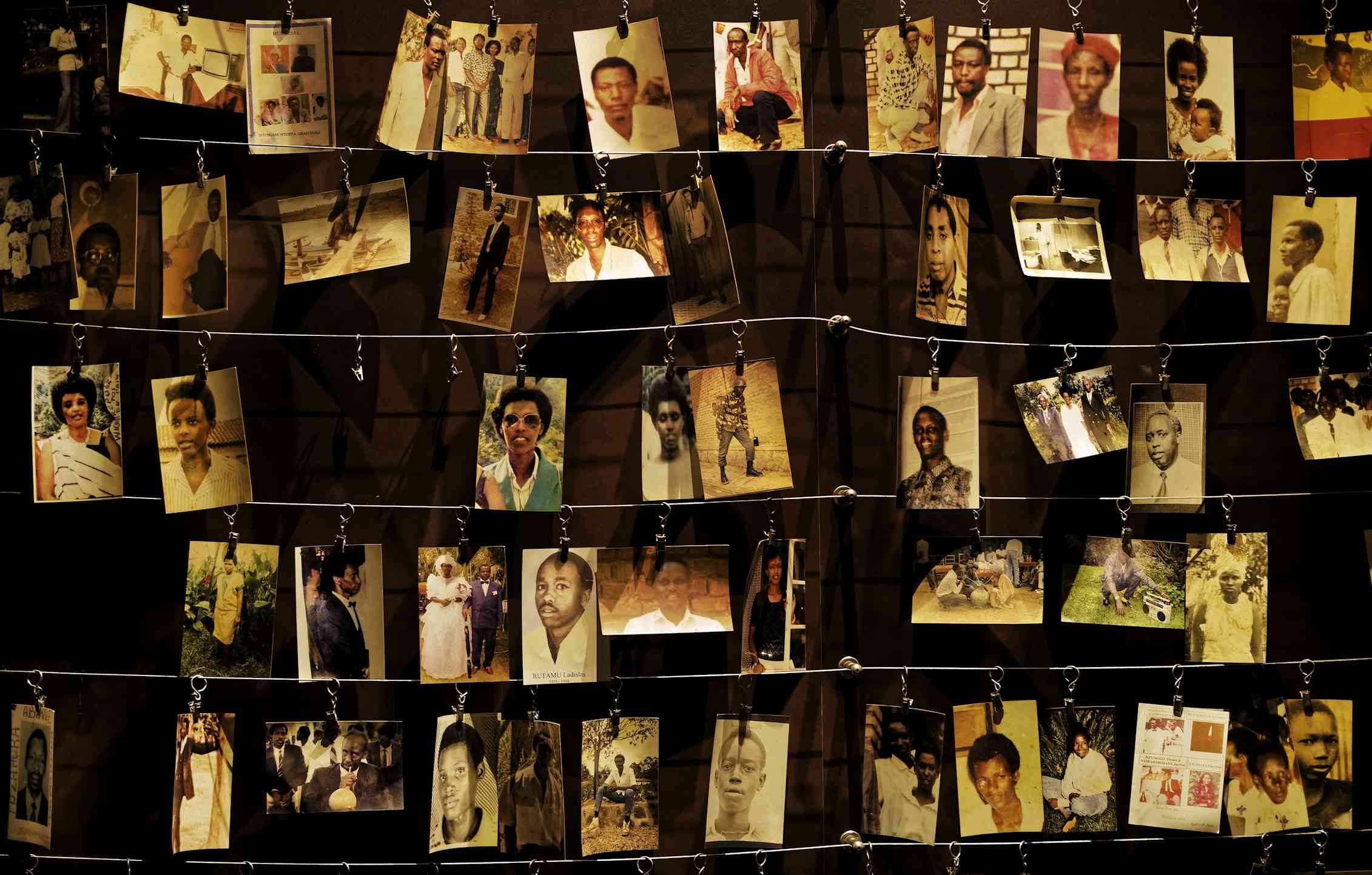

Still Life With Bones is a timely reminder of the legacies of war and genocide. This month, Rwanda marked the 29th anniversary of the start of the genocide in which neighbours killed neighbours, leaving almost one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus dead.

As in Guatemala, most were slaughtered with the machetes kept around the house for harvesting crops: “a tool of life [was] made a weapon of death”.

Hagerty’s book is a lyrical and powerful meditation on the meaning of justice, grief and ritual. It speaks of her haunted and fascinating travel through time and places, interrupted by the dead and the living.

Told in visceral vignettes, it is a painful reminder that once war is over, the new war begins: for justice, compensation, and a proper burial of the dead, “but this time with ritual and a name”.

Olivera Simic does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.