Merve Emre: Why Going Viral on Twitter Makes You Non-Human in the Public Sphere

You’re tuning into another dimension. A dimension of tweets and the writers who send them. You have just now entered the Twitterverse. Each week, Gabe Hudson welcomes one of his favorite writers and pulls four of their tweets. The guest reads one of those tweets out loud. Then Gabe and the guest use that tweet as an entry point into a conversation designed to illuminate the writer’s heart and mind. Rinse, repeat. Presented by Literary Hub and Best Case Studios.

*

Merve Emre is a literary icon for the digital age, a professor at Oxford University, and a contributing writer to the New Yorker. She’s the author of several award-winning books and recently served as a judge for the International Booker Prize. By any metric, Merve is some kind of genius, a wunderkind. And Merve’s Twitter feed makes the case for Tweets being little works of art that form a kind of jigsaw portrait of the writer.

So Merve and Gabe crack open her Tweets and get into it. They chop it up about Merve’s journey from Turkey to Brooklyn as a young child. What was it like for her family to live in Park Slope in the early 90’s? How did she break her arm that one time as a kid, and how does that event inform who she is today? What is the texture of Merve’s heart and the nature of the fire therein? Also, can a podcast episode be a work of art? In a surprisingly intimate conversation, full of joy and jokes and rare candor, Merve and Gabe attempt to answer these questions. Strap on your seatbelt, because this episode goes like a bat out of hell.

4-yr-old [very patiently to woman trying to push past him on the street]:

I’m not a pigeon or a seagull, I’m a little boy with small legs & I’m walking as fast as I can.

— Merve Emre (@mervatim) July 5, 2020

Merve Emre: That was my four-year-old. One thing that I am amazed by every time I go out in the street is the inconsideration, let us say, that many adults show not just toward one another, but often toward smaller creatures, whether those are little boys or pigeons. And I think that, in general, children are more sensitive than we probably give them credit for.

So this was my four-year-old, who had probably seen someone chasing or shooing pigeons out of the way and felt similarly shut out of the way by a woman who was trying to push past him on the street. He was like speaking up not just on behalf of himself, but on the pigeon and seagull community as well. I think it’s cool.

Gabe Hudson: Yeah. He’s like the Lorax, who speaks on behalf of the trees, but he’s speaking on behalf of the things that shit indiscriminately on the street.

Merve Emre: When I was a kid, I have a very vivid memory of moving to the United States from Turkey with my family.

Gabe Hudson: How old were you, may I ask?

Merve Emre: I was four. We were living in Park Slope before Park Slope was what Park Slope is now. So this is the early nineties and living very close to the public library there, the one in Grand Army Plaza, which I used to call Grand Armory Pizza and Beer. And I remember going to that library and trying to take all of the American Girl books and all of these Roald Dahl books with me and being devastated to learn that you needed a library card, that you couldn’t just walk out, that you had to apply and wait for a library card to come. And this is one of those great moments of childhood disappointment that is forever imprinted on my brain. I mean, I think that’s why Matilda stands out for me, because there’s no real child at the center of that book. There’s just the desire and the capacity, the ability to read.

*

When I was five, I broke my arm jumping off a picnic table & didn’t tell anyone about it until my dad noticed that my arm was, well, hanging at a strange angle. So, yes, this might be the role I was born to play.

— Merve Emre (@mervatim) April 1, 2020

Merve Emre: I remember as a child, I was always very afraid that I was a burden. I was very afraid of being a burden. I think that, you know, when my parents moved to the United States from Turkey, they were already fairly established in their professions. When they were in Turkey, they were both physicians and they had to start their training all over again when they came to this country. They had very little money and the first apartment that we lived in was not in Park Slope, though I can’t remember which neighborhood it was.

And now if you ask my parents at that time, they had so little money that they couldn’t pay however much the subway cost, $0.50 or whatever it was to take me to school so my dad would carry me on his shoulders for almost 30 blocks anyway. So I think I was always worried about being a burden because it seemed like my parents had way bigger problems between moving to a new country.

My father didn’t speak any English. I think my mother used to steal beans from the hospital cafeteria. … And actually I found this copy of a book that my first grade teacher had inscribed to me, because I guess they’d given it to me as a gift at the end of the year. And it said something, too think that you showed up in this class not speaking a word of English, and now you can read and write like a pro.

*

The last time I was this happy: pic.twitter.com/pCYd0cHuvT

— Merve Emre (@mervatim) June 17, 2022

Merve Emre: This is probably a picture that my grandmother took, and I’ll leave it to you, Gabe, to tell me whether you can see the person I am now in this picture or not.

Gabe Hudson: I actually can. I see it in the eyes. And also, you just have a kind of light about your countenance, which I think is present here and then also present currently.

*

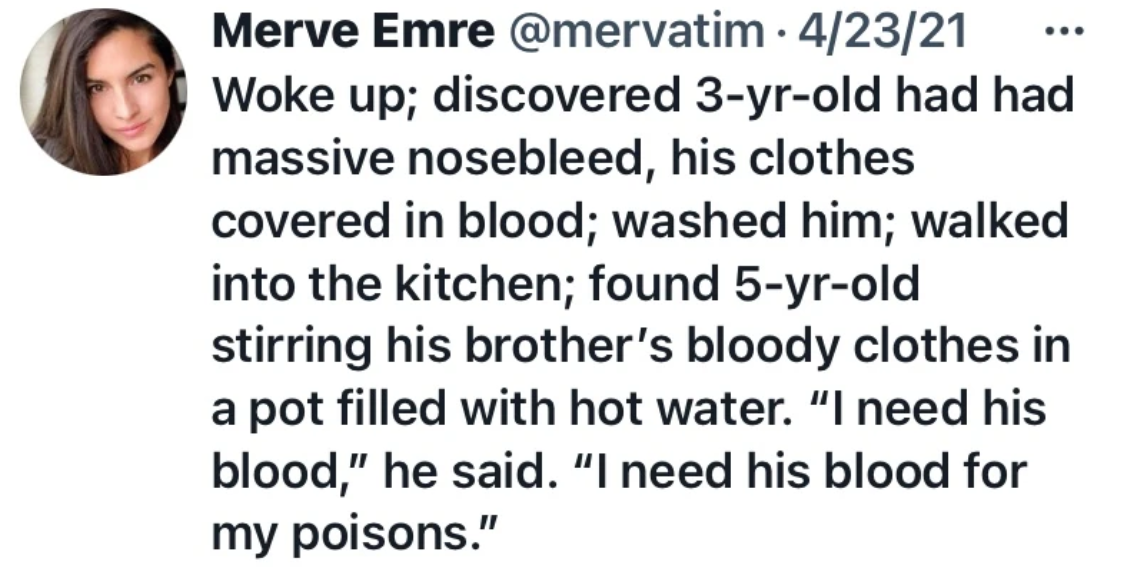

Merve Emre: I tweeted this. I set it aside. I go back and there are just thousands upon thousands of likes, retweets. I think by the time I had deleted it and—I’ll tell you in a second why I deleted it—by the time I deleted it, it had somehow ended up on The View … and ended up in the British tabloids as evidence of people turning to sorcery during the pandemic.

Gabe Hudson: Oh, my gosh.

Merve Emre: I think by the time I deleted it, it had something like 623,000 likes. It was an extremely strange experience for me because I think one of the things you realize when something really goes viral in that way is the degree to which you become completely not a human to the public sphere… You become totally nonhuman to the Twitterverse. You are no longer a human being who is capable of having feelings that can be hurt. Your children are fair game. Your whole life becomes fair game to completely lunatic people.

People writing to me and be like, let me give you a tarot card. Reading your son’s nosebleeds might mean that he’s going to die very soon. … How could you not call 911 when your child woke up with it? Like people who just don’t know anything about children being like, call an ambulance. Or people being like, you lying bitch. You horrible bitch. Why would you?

I was just completely stunned by this, in part because it just didn’t seem that weird to me. My kids do lots of weird stuff, but I eventually just deleted it because I realized that a year had passed between when I tweeted it, and in that year I was still having people commenting on it and still getting bizarre people writing to me.

__________________________________

Episodes of Twitterverse will be available for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Merve Emre is currently a Distinguished Writer in Residence at Wesleyan. She is working on a book called Love and Other Useless Pursuits. (November 2022)