Don’t Buy the Six-Dollar Cauliflower

A few weeks ago I went to an office supply store to buy some envelopes big enough to fit the construction-paper birthday card I’d made for my friend.

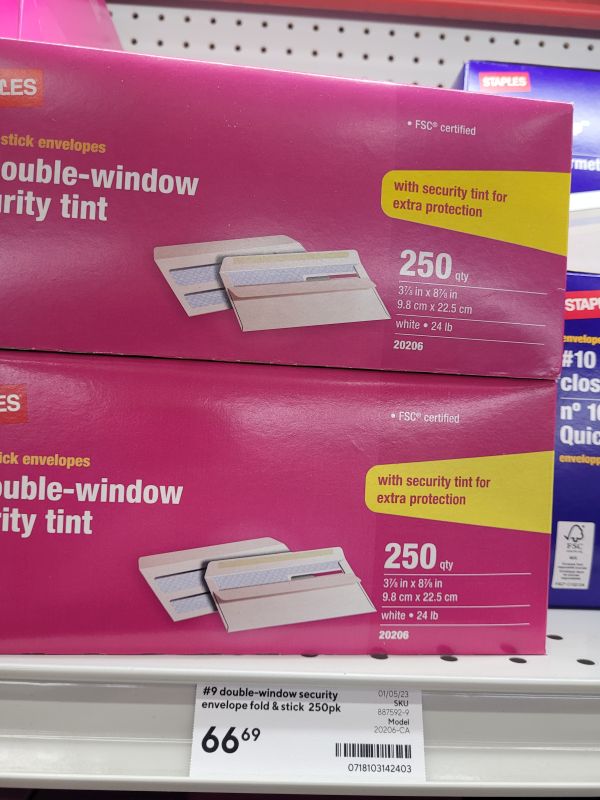

Pardon the language, but the prices were fucking ludicrous:

Thirty-seven dollars for a 50-count box of 9×12 envelopes.

Forty-six dollars for a 100-count box of slightly smaller ones.

Thirteen-something dollars for a 25-count package of the half-size ones.

The last package was the cheapest viable option for me at this establishment. Unfortunately I had left mailing the card till the last possible day. Evidently, I’m very accustomed to being a city-dweller with disposable income in a consumer economy, in which every minor item I need can be had by taking nine minutes out of my schedule to swing by some store somewhere.

But thirteen dollars! For twenty-five folded-and-glued sheets of paper. Or really, for one folded-and-glued piece of paper — the rest will probably sit in my stationery box forever.

I should have said no. Standing in the aisle, dumbfounded, I considered making my own envelopes. I have paper, and glue. I can fold.

There’s an important detail about this particular birthday card that partly explains the dumb decision I ultimately made. Three weeks prior, my friend’s partner had sent me three irreplaceable pieces of a custom-made jigsaw puzzle, which my friend was supposed to receive in instalments, by mail, from various friends, and assemble it on his birthday.

I was determined not be the one to ruin this heartfelt but precarious scheme by failing to get my pieces there. Therefore this envelope absolutely had to be mailed on time, and had to stay intact, so I couldn’t risk making my own franken-velope that might disintegrate en route or clog the mail sorting machine.

Of course I considered taking my business elsewhere, but on this particular day I hadn’t budgeted time for comparison shopping, plus I suspected I’d find similarly ludicrous prices at the competitors. I thought about driving a thrift store on the other side of town, known to sell Ziploc bags of random stationery for a dollar. But I couldn’t be sure I’d find what I needed there, and I could not bear the thought of returning to Staples knowing I would be paying thirteen dollars for an envelope. So Staples won the standoff, because in that moment, due to my own poor choices, it seemed worth thirteen dollars to get this unpleasant dilemma behind me.

And thus by submitting to the tyranny of inflation, I became its cause. This was wrong and pathetic and I vow never to do it again. It is a lie that I needed a thirteen-dollar envelope. Do not believe it.

Consumers complain about the creep of inflation as though it’s some impersonal, natural force, like tidal flooding or high winds. But it’s driven by human choices. Some of it’s surely due to orchestrated price-fixing, artificial shortages, and other corporate-side conniving. I have no idea how much can be attributed to those things, but I do know that some of the inflation, maybe enough of it to make all the difference — comes from the sort of consumer-side entitlement I demonstrated during my errand run that day.

It wasn’t just unwise to say yes to the ludicrous price they were asking, it was wrong. I paid them to keep their prices ludicrously high.

We commit this sin anytime we buy anything we don’t absolutely need at a price we think is “too high.” Too high for what? Too high for me to buy it, or just too high for me to buy it without grumbling about inflation?

At my local supermarket, cauliflower is $5.99 a head right now. I’m curious who’s taking them up on this offer. Who finds it to be a favorable deal? A cauliflower floret the size of a child’s fist cannot possibly be worth a dollar or more to the typical grocery consumer— that is, to any of us whose household budgets are meaningfully impacted by grocery prices. Do not buy it. Do not buy the six-dollar cauliflower.

The six-dollar cauliflower is six dollars only because enough people agree that they would rather have an unremarkable head of cauliflower than six dollars. It’s not because the grocery gods determine by fiat what people will pay.

Theoretically, everybody has an “enough” point. Most six-dollar-cauliflower buyers really would refuse to put a fifteen-dollar cauliflower in their cart. I hope.

What I’m suggesting is that our “enough” point is often a lot higher than we think it is. The average consumer doesn’t draw hard lines easily enough, and I’m assuming it’s because we are very attached to getting exactly we’re used to getting. We begin our price-related griping long before we change our behavior — long before we start voting the high prices away — and retailers know this.

(Note that by “we” I mean middle class consumers that complain about inflation and keep buying things at stupid prices like I do. You know who you are.)

The retailers know we’re confused about our own level of tolerance. How many of us have complained that the current prices for Thing X or Service Y are “crazy” — I’ve had “enough” of these insane cheese prices! — yet continue to demonstrate that we’d rather have the cheese than the money. We continue to pay the “unacceptable” prices because we actually accept them.

There are truly essential purchases, of course. You need to buy the gas in order to keep the commute going, and everything depends on that. Inflation is indeed creating real, external pressure on households that cannot bear it — but we know that and talk about it constantly. What we talk about less is how much of the pain of inflation is inflicted on ourselves and other struggling consumers by our own propensity to accept prices we know we should reject.

In my case, I think it’s because I tend to view the prices of the things I buy as “the cost of living” — the total amount of money the act of “living” currently extracts from me, given all of the envelopes and cruciferous vegetables I feel I need in order to live life as I expect it to be.

A more accurate and more empowering way to view prices is as offers. The supermarket isn’t charging six dollars to the cruciferously-inclined among us, as though we’re being arraigned and fined for the identity-crime of being cauliflower-likers. They are offering cauliflowers to anyone who likes them more than they like six dollars.

It’s simply a shittier deal than we remember being offered in the past, and we should not take it if it is not favorable. Unfortunately for us, the people offering it understand the gravity of our living habits better than we do. They know we’ll probably just grumble a bit and take the deal anyway.

Ideally, every time we see a posted price, we should imagine a question mark beside it. The retailer is the questioner, and you are the answerer. Imagine the price tag is leering at your wallet, propositioning you, the free and sovereign keeper of the treasury — “Hey, that six dollars you’ve got . . . can I have that?”

***

In other news: in response to the comments on last week’s article about phones-as-virtual-cigarettes, I’ve started a new experiment. View the experiment page here.